As the new academic session was set to begin in April-May 2020, the COVID-19 outbreak disrupted all educational activities in Nepal. Uncertainty grew, and the lockdown imposed to prevent the virus's spread continued to disrupt students' learning.

How can we improve students' learning processes during these difficulties? How do we hold teachers and relevant institutions accountable for children's education? How have others around the world addressed this issue? What steps can we take in Nepal? These questions led us to explore potential solutions.

The options, including digital platforms, radio, TV, and software applications, were being discussed. We did our best within our resources and access. As we discussed different options, we concluded that either teachers themselves or the local government would be the best people and institutions to start implementing the available resources to recalibrate children's learning. EduKhabar encouraged those who did their best and highlighted the available options for those unable to make efforts to improve children's education.

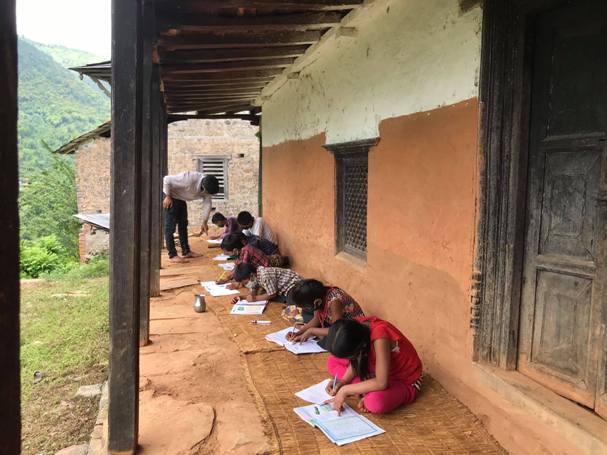

Almost all the community school teachers were at home. Only a handful were trying to contact their students through various available methods. We began hearing stories of teachers who started meeting their students in public spaces.

We published expert opinions explaining how learning could proceed despite school shutdowns. These insights helped teachers confined at home develop new ways to keep students' learning ongoing.

While sharing these ideas, some experts also discussed ways to integrate technology into teaching and learning. Schools in accessible areas—especially private schools—had already begun offering online classes to their students. But how were public schools supposed to start teaching? There was no clear plan. Even though the Ministry of Education promoted audio and video lessons that it had prepared, these classes were not easily accessible everywhere because of Nepal’s geography and the economic and social conditions of many parents. The reality of rural areas, where people often have little or no access to technology, was equally true and could not be ignored.

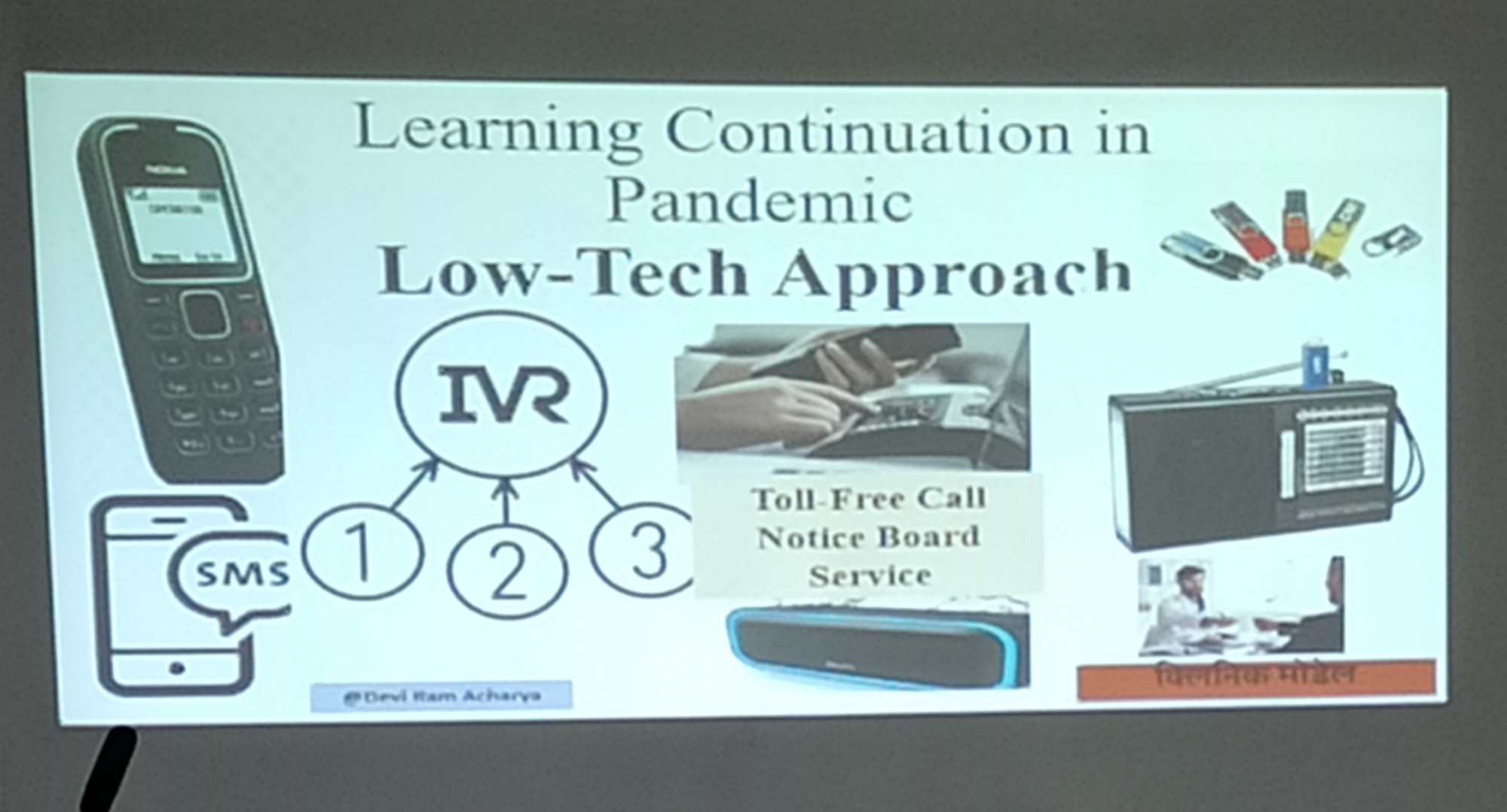

At such a time, how could we make use of inexpensive and widely accessible technology? Could teachers and students begin communicating even through a basic “TUKTUKE” mobile phone, not just Android smartphones? These were the questions on our minds.

Deviram Acharya, who has been active in the field of education, was discussing on social media how students could be connected to learning using an ordinary, low-cost mobile phone by purchasing the "CUG Pathshala package" introduced by the government through Nepal Telecom.

We also published Acharya’s idea. After it was published, the main question many people asked was: "How can teaching and learning happen on a mobile phone?"

Not just doubts—questions filled with disbelief started coming in. When the whole world had shut down, did that mean children everywhere would stop learning? And for how long would learning remain halted?

Exploring the Learning Methods Used During the Pandemic

Meanwhile, EduKhabar got in touch with Dr. Uttam Sharma, who was deeply concerned about students’ learning. Sharma had already been having discussions with Acharya, as he had been informally studying how learning was taking place around the world during the pandemic. We met online for further conversations.

By this time, schools had begun reopening, implementing safety measures to protect against COVID-19. Dr. Sharma discussed practices used in Bangladesh to reduce learning gaps and losses caused by the pandemic. Around the same period, we connected with Professor Asad Islam from Monash University in Australia. After some discussion, I received an email from Professor Asad as he was also also very enthusiastic to apply his ideas in Bangladesh to connect children to learning through simple, basic mobile phones.

Not a smartphone, not an app, not the internet — just learning through a basic “TUKTUKE” mobile phone call!

After several rounds of emails, One day i received a Zoom meeting link.

With a mix of curiosity, doubt, and excitement, I joined the online meeting. Instead of explaining the project or the technology, he asked questions like: What did EduKhabar do to support children’s learning during the pandemic? What changes did our efforts bring? What did not work? What did we realize was necessary?

I shared the examples we had collected about how teachers, schools, and local governments could support children’s learning even when schools were closed. A few weeks later, we joined a cross-country team with partners from Bangladesh and Pakistan. We were all working toward a shared goal: reconnecting children to learning disrupted by the COVID pandemic. The team from Bangladesh shared their experience with recorded lessons and the technical side of creating an Interactive Voice Response (IVR) system.

Professor Asad took an active part in all these meetings. He did not behave like a master but more like a colleague, and he explained the project clearly.

We held many discussions about the problems and the possibilities. Amid uncertainty and doubt, we finally decided to develop an IVR learning system that would teach children through basic mobile phones. EduKhabar’s team moved forward with this work together with Professor Asad and his team.

We requested that Sharma and Acharya join and contribute their expertise. They willingly volunteered for the initiative.

Class selection

This was a project we were starting as a pilot. It was natural for people in urban areas—who increasingly had internet access and were accustomed to online tools—to be skeptical of learning through a basic mobile phone. However, our goal was to work with communities that lacked internet access. In other words, our target group was children studying in community schools in rural areas where access to technology was very limited.

But which grade should we choose? This was a serious question. Students in Grade 8 face final exams administered by their municipality, and Grade 10 students have their board exams conducted by the National Examination Board. These grades come with heavy exam-related pressure, leaving little room for learning-focused activities. So, we decided to select Grade 9 students for this initiative, who later movecd to grade 10.

Assessing the students’ learning level

After selecting the students, we discussed how to develop the learning materials for them. An analysis of school-level exam results showed that students generally struggled in English, Mathematics, and Science, so we decided to prepare lessons in those subjects. However, creating lessons without first understanding the students’ current learning level might make the materials unsuitable. Therefore, we chose this sequence: first select the schools, then assess the students' learning levels in those schools, and only afterward create lessons tailored to their needs.

Selecting Schools and Getting Approval from Government Authorities

Our priority was to select schools in relatively remote areas—places where internet access was limited but mobile phones were common. It’s natural to picture far-off villages when we think of “remote areas,” but we also needed to be realistic, given our limited resources.

Therefore, in the first phase, we selected community schools from 24 municipalities in nine districts including 16 municipalities in five districts around Kathmandu that were lagging behind in learning, and in the second phase, 8 municipalities in four districts in Madhes and Koshi provinces. We covered 235 community schools in these areas. (The program was implemented in 223 schools, excluding some schools with fewer than 15 students.)

We selected these schools based on our informal review of the students’ economic and social situations and their limited internet access. We also chose municipalities where the education staff were relatively supportive to facilitate coordination with the schools. We obtained formal approval from the Centre for Education and Human Resource Development, under the Ministry of Education to evaluate the learning levels of students in those areas.

Due to limited resources, we chose only two subjects—English and Mathematics. To evaluate students in these subjects, we developed questionnaires with the assistance of community school teachers and subject experts. Enumerator assigned to each school received the necessary training.

After completing enumerator training, they carried a bag of questionnaires prepared for students, parents and schools and traveled to each school.

They didn't just assessment the students; they also gathered information on the parents’ economic and social conditions, as well as the school's overall situation. This was important because we needed to verify whether parents had mobile phones that could later be used to listen to the audio lessons. Additionally, they collected the parents’ mobile numbers. This would enable the IVR audio-learning system to automatically call the students when they dialed in later, ensuring they wouldn't have to spend their own money.

Assessment, Development of Audio Text and IVR System

After collecting the students’ assessment copies, we assembled a team of subject experts to review them. Once the students’ learning levels were confirmed, we decided to develop lessons for only two subjects that matched those levels. For creating the English and Mathematics audio lessons, we selected teachers who are experts in those subjects. They divided the essential learning content into 72 topics for each subject, ensuring that the minimum learning requirements were covered. In other words, each subject would have 72 audio lessons, and the topics were chosen, with lesson plans prepared accordingly. Because long lessons can feel tiring to listen to in audio form, each lesson was designed to be no longer than 10-12 minutes. Then, the recording of the audio lessons began at the radio station.

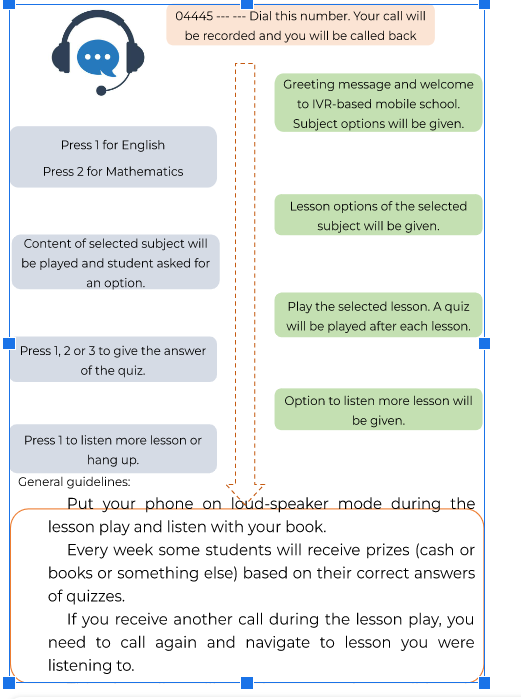

During this time, the development of the IVR system was also progressing. After discussions with the telecommunications company, it became clear that building the IVR system ourselves would be very costly. Since our goal was to support children’s learning with limited resources and at the lowest cost, minimizing expenses became our main focus. While exploring options, we discovered several organizations that had already developed IVR systems. One of these companies agreed to work according to our concept. We signed an agreement and started the work. The audio lessons were uploaded into the IVR system, and we conducted trial tests as a sample. We were very careful to ensure that listening to the lessons would not place any financial burden on parents. The system worked: when someone called to listen to a lesson, a callback was automatically sent to the same number. Because of this callback, the listener did not have to spend any money. The cost of the callback calls was paid by us to the company, which then paid Nepal Telecom.

The model of teaching over the phone from Kathmandu and the selection of tutors

Out of the 7,179 students we assessed, we could not include all of them in the IVR classes. Since this project was a pilot with limited resources, we couldn't enroll every student. Instead, we decided to give IVR access to students from 148 schools across nine districts. Among these schools, students from 74 could call the IVR system themselves and listen to audio lessons. Students from the other 74 schools would not only listen to IVR lessons but also receive direct phone-based tutoring from tutors based in Kathmandu. The idea of learning over the phone surprised many, and the question “How can someone teach through a phone call?” still lingered for us as well. For the two subjects, we selected eight tutors per subject—sixteen in total. We chose young tutors who were comfortable speaking on the phone, eager to teach, and proud of their profession. When Professor Asad visited Nepal, we organized an orientation session for them in his presence.

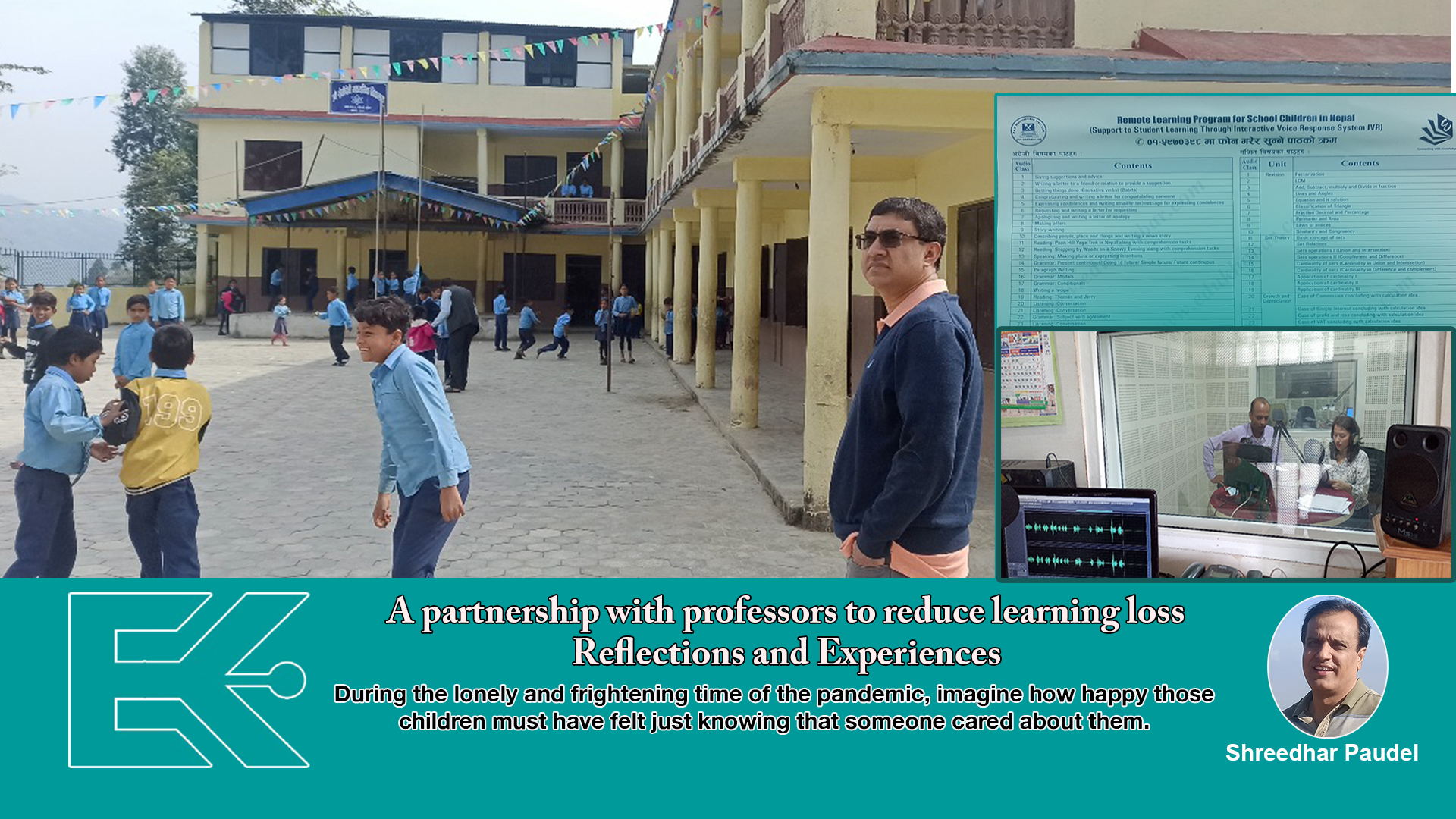

The tutors ready to engage in this new kind of work had many questions. How is teaching possible over the phone? How can students be taught effectively through a phone call? After Professor Asad explained the concept, their enthusiasm clearly showed. Each tutor was assigned to work with no fewer than an average of 142 students. This was also the time when Professor Asad came to Nepal to directly observe the schools we had selected. Traveling with us along rural, rough roads, he visited the schools. He experienced Nepal’s rural lifestyle firsthand and also observed the schools that had just reopened after being closed for many months.

He was very concerned about people’s access to mobile phones and the availability of network signals in rural areas. Wherever we went and whomever we met—teachers, parents, or students—he asked each person about their mobile phone access and connectivity.

He wanted to be sure whether students would actually be able to access the IVR system.

Professor Asad was deeply involved in understanding the realities of Nepali daily life:

Who controls the phone in a household?

How often is the phone charged?

Do parents take their phones to work, or do they leave them at home?

Do fathers take it to their workplace, or do mothers use it themselves?

He asked countless such questions to get accurate answers. He also spoke with teachers about the challenges they were facing due to learning losses caused by the COVID pandemic and he chatted with children about their schools. Everyone we met seemed moved by the concern and humility shown by a professor from a renowned international university toward the everyday realities of rural Nepali life.

The model of student access to the IVR system

After Professor Asad returned from visiting the selected schools, we focused on confirming whether the IVR system would actually work. We gave IVR access to 35 students from a school in Lalitpur as a sample and tested the system. After they listened to the lessons, we collected their feedback. They were happy with the experience.

As mentioned earlier, the parents’ phone numbers had been entered into the system so that when they placed a call, the IVR system would automatically call them back. Of the students who were granted access to the IVR system, 1,157 could call and listen to the audio lessons independently. Another 1,142 students not only listened to the IVR lessons but also received a phone call from a tutor in Kathmandu once every 14 days. We did not include the remaining students in any group intentionally, as we wanted to observe whether there would be any difference in learning between students who participated in the audio classes and those who did not. Therefore, the students were divided into three groups.

Practice in using the IVR system

The audio lessons were prepared, the IVR system was developed, the students who would receive IVR access were chosen, and the tutors who would teach by phone from Kathmandu were ready. The remaining task was to teach the students how to call and use the IVR system. For this, we planned to meet the selected students in person at their schools and train them individually on how to operate the system.

Enumerator were sent to the field to distribute pamphlets to the selected students. These pamphlets explained how to use the IVR system and listed the order of the Mathematics and English lessons.

The enumerators who went to the field first updated the parents’ phone numbers, since some had changed. After spending a week teaching students the technical steps—how to call the IVR system and how to listen to the lessons—we gradually started uploading the audio classes into the system. Within two weeks, all 72 lessons for each of the two subjects were uploaded.

Every 14 days, the tutors began calling their assigned students.

The challenge posed by students’ low engagement and the efforts made to find solutions

This campaign, which started on a small scale to help recover children’s learning loss during the pandemic, was completely new. We were very excited. The feeling that we were part of something innovative motivated us. But when the first set of data came in, we felt deeply discouraged. Very few students called the IVR system. Still, we did not give up. Edukhabar’s staff were fully engaged and also made sure every parent is informed about their children’s access to the IVR lessons. Our staff discovered several things. Many parents often changed their phone numbers. They frequently switched SIM cards to get new data packages, which caused their previously registered numbers to stop working. In many households, parents took the phone with them to work, leaving the children at home without access. In some places, the mobile network was barely functional. And some parents were suspicious from the start—wondering who was calling their children and why? Their concerns were understandable.

Teachers mistook the program for a competitor

When we contacted some parents, they told us that their children’s teachers had instructed them not to listen to these IVR classes and not to answer calls from the tutors. Students also shared similar experiences with the IVR tutors. The campaign, which we started with good intentions to reduce learning loss, was seen by some teachers as a competitor! We realized that this misunderstanding by teachers also discouraged students from listening to the IVR lessons. The students were far from us and many factors were beyond our control. Still, the tutors kept calling them on scheduled days, and though our staff maintained communication with parents to motivate them to use the IVR system. This effort continued for six months.

The sadness brought by the final results

After developing the IVR system and engaging students in learning for six months, we again sent enumerators to the same schools for the final assessment.

On the scheduled dates, the enumerators completed student assessments and filled out the parent questionnaires before returning to Kathmandu. The subject experts reviewed the students’ answer sheets in the same way they did at the beginning.

When the results were announced, there was no significant improvement in students' achievement in English and Mathematics. We felt months of effort ended without any measurable students’ learning progress. While some students had dropped out during the process, and some others did not turn up for the assessment, w total of 6,019 students took part in the final evaluation.

To be honest, the students’ results were deeply discouraging for us. It was hard to believe in the begining

So much time, so much sincere effort and even with limited resources, a meaningful financial investment… Yet we had nothing significant to show for it.

After seeing these results, we felt anxious: How would Professor Asad react? This question increased our stress. He called an online meeting with the entire team.

We looked at the disappointing results together.

To our surprise, instead of criticizing us, he thanked us for our honesty and hard work.

I still remember it clearly—he smiled in the same calm way and said, “We have learned something valuable.”

It was only then that we realized the true purpose of this initiative. The project was not just about teaching—it was about hope. During a time when learning was breaking down because of the pandemic, our effort also served to encourage children, telling them there are many ways to keep learning and that they should not lose courage.

We believed the reasons for failure were obvious: weak phone signals, parents frequently changing their phone numbers, students’ limited access to phones, and student's disturbed mental state after the pandemic, the pressure of formal exams when schools reopened after a long gap, and teachers’ doubts about alternative learning methods.

But instead of focusing on these, Professor Asad shared his own conclusions.

He identified many obstacles in the rural education system—challenges we had seen but hadn’t fully examined. More importantly, he pointed out something in the results that we had completely overlooked. Referring to the students who received IVR access and tutor calls, Professor Asad said: During the lonely and frightening time of the pandemic, imagine how happy those children must have felt just knowing that someone cared about them. He continued, “Because of our phone calls, they probably did not feel alone. We thought our lessons didn’t reach them. But imagine the comfort they felt realizing that somewhere, someone was thinking about them and checking on them.”

It was only then that we realized the true purpose of this initiative. The project was not just about teaching—it was about hope. During a time when learning was breaking down because of the pandemic, our effort also served to encourage children, telling them there are many ways to keep learning and that they should not lose courage. Seeing it from this perspective changed our entire understanding of what “development” means.

For years, we believed success was measured by visible results: good scores, increased attendance, and larger numbers. Professor Asad completely changed my perspective on that idea. When a project doesn’t produce the expected outcomes—despite genuine effort—it still teaches us valuable lessons. He helped me see that research and fieldwork aren’t separate worlds. When both are approached with patience, respect, and curiosity, something truly innovative can emerge.

Among the 16 tutors who taught students, some still receive phone calls from their former students. Even after finishing their school level, some students continue to call and ask questions they still don’t understand.

Madanbabu Phuyal, a mathematics tutor, said that some of the 144 students assigned to him still call and continue trying to learn.

“They still call me with their questions, and I teach them,” said Phuyal (who is now teaching at a community school in rural Nepal) over the phone. “Thank you for giving me the opportunity to experience something new and to stay continuously engaged in teaching.”

Prerana Kattel, an English tutor, shared that some parents of her former students still contact her, ask about her well-being, and request her to teach their children a little more.

Isn’t it an achievement in itself that a child from a remote village still sees our effort during a difficult time as a meaningful learning opportunity?

प्रतिक्रिया