Introduction

When I was invited to speak to you here today, and as it often happens to me these days when I think about writing anything at all, I was kind of lost. I then asked Google Guru the question, “Why read?” and there popped up maybe a hundred or perhaps thousands of entries. The first entry was from a site with the title, “17 Reasons to Read”. Seventeen reasons were too much for me to handle, really. I certainly did not wish to take that road for my presentation here. I did not wish to describe why one should or should not read. Nor did I wish to tread on what to read and similar other questions either. Sudarshanji’s (Member of SIKAI Foundation_one of the organizer of Reading Conference) email, however, gave me a lifeline. Essentially, he said I could write about myself – my own journey into reading. That opened the door for me. Sudarshanji, thank you so much.

Reading as Braiding Together

At the outset and before taking you to a trip on my reading experience, I must emphasize that the personal is also parochial. I am worried how my experience will resonate or fail to do so with some of yours. In particular, my reading has been shaped by the particular slice of society and historical period I grew up and find myself in. In addition, my reading was also shaped by what I thought I was becoming, what I have become and remain in the process of becoming. I think this applies to each of you as well – that our reading is shaped by how our life is structured, the forces that envelop us as well as by the fractures and perforations we seek to inflict upon that envelope.

In my case and more concretely, a lucky chance fell upon me early on to take a gamble on becoming an academic and a sociologist at that. I was pleased to take the chance and it has, luckily enough once again, paid off – inasmuch as it launched on a career I wished for. I fully agree with the idea that using up your life in a profession that you like is one of the greatest gift there could be.

One of the drawbacks of becoming an academic, however, has been that I most often do not, as some of you do, read primarily for enjoyment. I do enjoy texts I choose and read, but enjoyment is not my primary motivation for reading. Apart from reading news, I mostly read in order to seek illuminating vantage points through which to view society and to comprehend the nature of a society and how it is changing. Great and novel vantage points and ideas give me goosebumps. Those instances often serve as addictive drugs and I intently remain on the lookout for such ideas. More concretely, I read rather prosaic texts on how the nature of individual life and nature of society are intertwined and how the flow of history together with the nature of economic, political and cultural relations play crucial roles in shaping each of us, including our birth and death, mobility and immobility, education and employment, caste, ethnicity and class, health and sickness, dress and hairdo, love and hate, hope and fear, desire and imagination, and so on. I hope that you will tolerate this particular bias of mine for the next 20-25 minutes. Hopefully, you will not doze off either.

I am not a voracious reader either. I read quite selectively. When I do read a text, however, I burrow deep inside it. I engage, as it were, in extended conversation with the authors(s). I seek the deeper implications of what is not immediately apparent. I ask how does that text change my perception not only about societies in Nepal and outside but also about myself. I believe that reading should not only provide be enjoyable, offer me information and knowledge, enrich my perception of myself and of the world around me and, finally, change me.

Strong reading enthusiasts, including in Nepal, consider reading to be inordinately important to life. A few even equate reading with a life worth living. Under this train of thought, the quality of life of the unread would be, to put it mildly, a bit less than human. Many, on the other hand, would not quite agree with such judgment. I include myself in this latter category.

The act of reading, of course, and as all human acts, is personal. Yet, it is also far more than personal. Reading is, simultaneously, also historical and social. The nature of reading – whether to read, what to read, whether the reading material is digital or otherwise, etc., changes across historical periods. Most human beings did no such thing as reading as recently as two generations ago. Those generations would include most of our grandparents. But many in those generations lived productive as well as intermittently enjoyable (as well as harsh) and often empathic lives. Reading, writing and printing began, to the extent that we know, from Mesopotamia to near East- including Persia - and Harappa, Mohenjo-daro and so on. Such inventions, inevitably, began to expand the domain of reading. In addition, printing, excluding block printing, was invented in China and other parts of east Asia during the eighth century CE.

I must note here that reading is not, as it is often portrayed, a non-social and solitary act. The reader is very often closely engaged with the text although the extent of engagement can differ by objective of reading, the nature of the text and the author and many other contextual matters. But there can be no completely unengaged reader. The fiction reader, for example, is often intimately engaged with the story and its flow, the diverse characters, an anticipated turn of events that might take place a few pages later and so on. One of the texts I currently teach to my students tells us that readers find their own selves in the characters of a fiction. Indeed, the text tells us that reading a fiction, a romantic fiction in particular, is often immensely enticing because the fiction offers the young reader an opportunity to identify oneself as the hero or heroine of the novel. I rarely read fiction these days but my engagement with most texts I choose to read is not any less engaged.

Writing, reading and printing moved to Europe much later. All this goes to show that Europe as a producer of the culture and technology of reading is a rather recent development. On the other hand, almost all of us gathered here are heirs to the modern European tradition of reading. This has had mostly good but sometimes ill consequences. Extreme valorization – and therefore ahistorical and uncritical - reading of Euro-American texts has led, for example, to Orientalist visions and judgments in the “West,” as was described so trenchantly by Edward Said. Indology, which is a form of reverse Orientalism, and which prioritizes texts and norms rather than actual practice, has had similar consequences all along the “Orient”. Among the ill consequences of uncritical readings, let me cite one here. It is a ploughed back frame of Indological thought – that has come to us via Max Muller, Rastriya Swayamsevak Sangh and Nepal’s own Brahminism – that some of us now are tagged with a race and eugenics-laden identifier, the (Khas-Arya). Not all reading, as such, ought to be valorized. Uncritical reading, in particular, leads to strange and unfounded as well as to personally and socially ill consequences.

As a footnote, I may also note here that that rampant uncritical and ahistorical valorization of so-called “eastern philosophy” – that also includes “eastern” culture, religion, etc. in Nepal and India - and perhaps in several fundamentalist Islamic countries – has retarded and severely slanted the reading of other cultures and societies. It is completely warranted to be proud about a glorious intellectual past as also to draw inspiration from it for further intellectual and political inquiry. But to keep gloating over it five hundred and more years of world-scale economic and political transformation and the relocation of world intellectual centers and to keep insisting that the “eastern philosophy” is the be all and end all of humankind is a historical nonsense. It also serves a faith - rather than democracy - inspired, caste-based and extreme right-wing political agenda. It is also inimical to reading and learning inasmuch as its zealots attempt to stifle inquiry by claiming that all or most of knowledge can and ought to be sourced in “holy texts” that were divinely authored (apaurusya texts) or were humanly authored during much different political, economic and cultural dispensations 2,000-600 years ago. As could be expected, even here, the preference of the zealots is not to the humanly produced, more recent and truly substantive texts, some of which in all probability gave rise to part of what is now labelled “Western philosophy and epistemology,” but to the old and apaurusya ones that often addled by faith-based, devotional and mystical digressions. Within the former, I bracket explorations in philosophy, epistemology, logic, linguistics, meditation, etc. that the Nyaya-Vaishesika, Sankhya, Yoga, Lokayata-Charvaka, etc. schools of thought. I should note that I am a near-complete novice on these literatures. I find them fascinating – not the least because part of what I learned in my graduate school was invented and authored as far back as 500-1,500 years ago – and the political-geographical, economic and cultural region I grew up in. I feel sad that much of the last half-a-millennium or so has been wasted in the shadow of the cult of Bhakti. A strong emphasis on the cultivation of bhakti dealt a blow to a culture of inquiry. Ever since, parents, teachers and the society-at-large have, instead, largely been pushing what I have recently started labeling ubacha sixya. Engaged and agentified learning and teaching, on the other hand, are relegated to the backseat.

It is difficult to assess when reading came to Nepal. Some of the settlements in the relatively prosperous low valleys and market centers might well have, to a minor extent, supported reading and writing, mainly among the royalty, priestly groups, revenue collecting families and traders. (The last group very probably was the most well read, not strictly in the manner of becoming proficient in texts but becoming numerically proficient, traveling through places, speaking to and transacting with diverse peoples and becoming worldly wise.) Much more recently, the bhasa pathasalas that sought promote literacy and basic arithmetic, in addition to laws, etc., were formed in a few locations in the country. The Durbar School was formed early on. But it remained solitary for long years. Later, mostly following the formation of a decolonized world and the close of Rana rule a few “English schools” came along in some Hills and Madhesh towns by means of mostly local private philanthropic initiatives. Eventually, the New National Education System Plan beginning 1970, laid the foundations of schools all across the country. In the 1980s, the final floodgate was opened – that of the of privately organized profit-making “boarding-yet-not really-boarding” “English” schools. Many of us gathered in this room started out as heirs to the New Education Plan and the private schools. Many of us acquired the opportunity to read and to impart a reading culture to our children because of these two social inventions.

In addition to history, reading is also shaped by the nature and specificity of our social life. Birthplace, gender, age, ethnicity, language facility, caste, employment status, income and class, education, profession, etc., and the nature of our imagination, aspiration, hopes, fears, agency, etc., all shape our reading. Reading, thus, is not so far off from the nature of social life we inhabit.

In essence, reading cannot be an exclusive act. It is not as if one reads and does nothing else. In addition, one cannot fully compartmentalize reading on the one hand and history and society on the other. A reader cannot keep reading without linking it to the past and present and to self and society. Braiding together of text, history, life and society is fundamental to the act of reading.

In order to further explore the significance of the notion of braiding, let me bring in the very powerful aphorism that we can draw from Immanuel Kant: We do not see the world as it is but as we are. Thus, the reader projects his or her own thoughts on to the text at least as much as the reader takes inform the text. The reader remains in constant dialogue with the text. It is not that a new text fully sinks in; rather, whatever sinks in remakes the old mind. The mind does not as much reserve a distinctive compartment for a new text as much as it utilizes the new text to refine what is stored.

That reading is selective is also clear from the fact that two persons who read a given text do not even summarize the text in the same manner. The two, also inevitably, review the text in at least partially incommensurate and possibly contradictory ways. Indeed, the same person “reads” a given text differently at different points in time. I read William Wordsworth’s “Lucy Gray” both at school and in college. Similarly, I read Lekhanath Poudyal’s “Pinjarako Suga” both in Grades Five and Nine. At each level, I read each of the poems in significantly different ways.

My story of reading

School days

I was not a good student at school. I was particularly weak in Math. I liked going to school and to meet friends there. But I often avoided reading books. Occasionally, I also wondered why I had to go to school every day and why I could not just walk around and play with my non-school-going friends or those who had pretended to be sick for the day. Of course, few of my classmates had anything like what we would call a reading habit these days. Of the very many subjects in school, I was fairly good in languages and in geography. In particular, I was told that I was good in the English language. If that was valid at all, some credit must go to Krishna Lal Shrestha, who was the ultimate genial teacher in my school. He loved and cared for his students. Most of all, he would habitually bring along to the daily class a pocketful of tiny and round colorful candies (guchchapipi) for his students. In geography, I particularly liked flipping over and over and “reading” a book on world map. I could really spend hours with that book even though it was not a required reading. On the other hand, I was utterly weak in algebra and geometry. One consequence of this was that I failed my SLC exams the first time around. I barely - really barely - scraped through in the supplementary SLC exams that followed four months later. I have since regaled some of my relatives and friends by reciting the story of how I managed to scrape through the SLC ordeal. It was a 30-day-long tuition session with a friend’s grandfather in my immediate neighborhood. The tuition fee was Rs. 30. And I scraped through with 30 marks in Maths. Thirty, if some of you are unaware, was the pass mark.

The months following my failed SLC exams were, however, also the days when I happened to inaugurate, so to speak, my initial reading days. I mean reading for personal enjoyment, that is. I suddenly became addicted to spy novels written in the Hindi language. One-book-a-day. Sometimes two or more books each day (and night). I had failed at the iron gate but reading spy thrillers was just great. I either had a book with me or I was at the playground. During the latter years of this period, I also diversified into English-language spy and other novels as well as non-fiction books.

Undergraduate days

I continued with my fiction-reading routine. In addition, I was now required to read texts related to my college courses. I was admitted to the College of Education, Tribhuvan University. As far as I am aware, the College of Education then was supported well by the Ministry of Education as well as the American government. The objective was to prepare competent teachers for high schools across Nepal. Several of my teachers there seemed to really like teaching and chatting up with students. Quite a few had acquired their Master’s degrees from a US university. One had a PhD from a California University, possibly the UCLA. They were the role models for us there. It was a sort of heady atmosphere where students were motivated to do well.

I think it is, at least initially, due to the teachers and the books there that I wished to become a college teacher myself. Becoming a good teacher and reading “many good books” became a wish that I nursed. It is, of course, the case that many other chances and options had to be negotiated in order to keep up with that goal. But, I must say, many other chances, events and options, for a career I had just started thinking about, gradually and more or less fell into place. One lesson I have drawn from this is that reaching a goal requires one to stand in a queue as one also puts in the required efforts. The queue is most often very long but then it can sometimes bifurcate, trifurcate and so on, thus shortening the distance to the endpoint. Not that I have reached any big-time goal. But I did start catching the rope I wanted to hold on to.

Most of all, I liked the college library. I was taken there on the first day of my college. I was so astounded to be in a sea of books. I had never seen so many books ever. In fact, I had no notion that there could be so many books, period. And the bookracks and the wide tables in the large sunlit room, were all gleaming. (I may note the college was housed in a Rana family palace – where the Hotel Radisson now stands - and the library had taken over the large living room there. I would later come to know that it was a middling kind of Rana palace but for me there it stood in all its splendor.) There were no dog-eared, dirty and flimsy books like I had at my home either. Instead, the books were newish, hardbound, mostly glossy, thick and downright inviting. I think I did handle a few books. I also read a few pages of the similarly inviting magazines there. I also walked along most of the racks. Possessing the gumption to patiently read books came somewhat later.

During the first year, I think I more or less sat still in awe of the library and books. I started flipping more pages in more books during the second year. The third year, I had a couple of inspiring teachers who taught Nepali and English languages in ways I was not accustomed to. My language teachers till then basically described and summarized the plot or main theme, relayed chhoto mane (meaning of words) and lamo mane (meaning of whole sentences), did the saprasanga byakhyas (contextualized explanations), and that was it. This new set of teachers, on the other hand, deemphasized all of those aspects and instead prioritized literary criticism. That one could overlay one’s thoughts over that of the very writer of the text was unknown to me. I found that immensely liberating - that I could think on my own – and including on subjects going much beyond literature. In a way, I found an amazing set of wings.

I then also started to enjoy reading books on subjects that were often removed from the ones I was required to study as part of my courses. The college moved to a different location – to Kirtipur – in my last year of college. The location and the buildings were great. The library itself, however, was located in a comparatively dingy hall. Nonetheless, caught up as I was with reading, and because it was the final year, I often took to simultaneously flipping 2-4 books related to the course plan, to read them together and prepare notes that I potentially could use in the exams.

Even though I was in college, the fright I has with Math during my school days would occasionally creep back on me. Counter-intuitively, this was not the least because I had become able to resolve some of the problems in geometry and algebra by means of mental math. In one of my little Eureka moment I could suddenly comprehend, while dribbling football on an enclosed playground, what Theorem 11 in my Geometry text had been trying tell me. The idea was very simple really. It merely said, any two sides of a right-angled triangle added together are longer than the third side. All it was saying, it dawned on me on the football ground, that it would be shorter and faster if I ran along the hypotenuse line than running along the other two sides of the enclosure. Similarly, it dawned on me that the symbols utilized in algebra, such as x, y, and z, were abstract variables that could be loaded with definite, concrete and pre-defined numerical values.

It came to me after a painful failure and 2-3 years too late but dawn it did. I had braided my math with my life and with the real world. As I played along my Eureka moment in my head over the years, it taught me lessons that I consider valuable for reading, learning and teaching. You see, I was under the impression throughout my schooldays and even following two years of college that points, lines, angles, triangles, etc. existed merely on paper. I did not “read” the text or the teacher well. More likely, my teacher was himself unaware that geometrical shapes and algebraic expressions exist or could fruitfully be conjured everywhere in life, right from the human body to the universe. In addition, I strenuously resisted learning algebra and geometry because I did not know - and had not been told - how the various algebraic symbols and geometrical shapes could be useful to the way I was conducting my life. If something is not useful, I reasoned, and I can distinctly recall that feeling even now, why bother at all?

The more relevant points here are: Engagement in reading is not always an individual act; with social support – from family members, teachers, extended-family kin members, neighbors, friends, etc., the experience of reading can be immensely enriched. Two, most reading invites reflection on the part of the reader. I say “most” and not “all” because reading has often been carried out in our culture with an unquestioning faith on authorial power, whether in classroom, liturgy, ideology, political party, political leader, etc., which is inimical to reflection. Reading aimed merely at memorization is completely unfriendly to reflection as well. I do not really know whether very young children can be as reflective as adults. But my own schooldays were spent rather unreflectively possibly because most such reading was done at the behest of my parents and teachers.

On the other hand, reflection obliges a reader to braiding. A reflective reader braids reading with one’s own life, society, history and a plethora of other domains of immediate and longer-term interest and duty as well as with imagination, hopes and fears. The reading process, sentence to sentence, paragraph to paragraph, and chapter to chapter involves self-reflection, juxtaposition, judgment, etc., when the cycle restarts again.

Graduate Days I

I went to India for to pursue my Master’s in Sociology. I had never heard of something called Sociology just a couple of months earlier to when I started my program. For various reasons, I was admitted more than a full month late as well. I was worried that I may not turn out to be a good student. I went about buying books and utilized the library facilities, and read a lot. In both the first and second year exams, I performed well. For the MA level, I thought I had become an accomplished sociologist.

In addition, I became a regular reader of newspapers. That afforded me a fairly detailed knowledge of Indian and world affairs at the time. (I should note that I have remained a news junkie since.) I believe it also helped me to hone my English language. The biggest regret that has remained with me, on the other hand, is that I made no attempt whatsoever to learn the Marathi language there. I was quite parochial then and spent most of my free time with a few fellow Nepali students there. I found out late that it was a no-no from the point of view of learning and growing up.

I came back to Nepal with a swollen head, so to speak. Mind you that a rude awakening and a reality check was just around the corner. I went to visit the head of the best social research agency in Kathmandu at the time. He spoke with me briefly and asked me to see his junior, who was a fairly well-known researcher there. The two of us chatted briefly and I was asked to prepare a write up on a subject of my choice and to report back in a week. I duly prepared the paper and went back to see him.

I had told him that one of the issues I really liked was the nature and dynamics of bureaucratic organizations. “OK, why don’t you write on that,” he had said. After I handed him the paper, he intently scanned through it. Then he asked me if I would be willing to accept a position one level junior to what I was expecting. My swollen head began to spin. I told him I would think it over and report back to him. Because my pride was badly bruised I never reported back to him. It is a different matter that I remained unemployed for nearly seven months after that and earned considerable flak from my family and well-wishers on that account.

I was stunned for a couple of days after that encounter. But as Steve Jobs said once, one can make sense of things only backwards or after the fact. But it dawned on me quickly enough that I had done well in my MA exams – only insofar as I was better compared to classmates. But that did not, by any means, imply that I had become a good sociologist. Two, and even more importantly, I had read a lot of books but I had not read Nepal. I knew the nature and dynamics of bureaucratic organizations as it was written in the books I had read. But I had not experienced or read about – and written about – the proverbial Singha Durbar. I had read the books but not society, history and the world. Thus, for me and at the time, a bout of faithful and close reading did not deliver. Indeed, in a way, it backfired. I had to read not closely and faithfully but tactfully and critically, and to braid reading with life and society and the multiple and disparate contours of changes in them. That encounter with epiphany will remain with me through my life as a lesson that I had to learn.

I have thanked the person who said “no” to me ever since. That person, more than any other, told me that a text was not a live and instructive text unless the reader juxtaposed it with the nature of society and world he or she was inhabiting. The text came to life and you could learn from it only if you were willing and habituated to engage in conversation with it based on your experience of your own self and your surroundings.

Graduate days II

I became a double-duty journalist for almost a-year-and-half after that. During the day, I wrote brief radio commentaries, where I was mentored by a highly competent boss. I simultaneously worked in a newspaper, where I mostly edited wire services till late at night. I was ready to leave for home only after I proofread the titles to news stories on the front and back pages during the wee hours of the morning. I also reported and wrote a few articles during the year-and-half I spent as a journalist. That experience helped me learn a bit more on Nepal and improved my English language comprehension and writing skills.

Immediately following my stint as a journalist, my luck struck once again. I was awarded a grant for graduate study in Sociology at a middle-ranking university in the US. Armed with the epiphany I noted earlier, I made up my mind to focus upon the nature and dynamics of real-world social relations that lay underneath the sentences, paragraphs and chapters in the books I read. To some extent I sought to apprehend the real world in company of my friends, their families, the storekeepers, and so on. That opened the door for me to engage in “conversation” with texts and authors, which manifested primarily by means of extensive comments I wrote on the margins of the pages I read. My books, some with shiny covers, in consequence, are very dirty inside with scribbles on many of the pages. I find many of my scribblings plainly stupid just a month later. I cross them out and scribble some more in the meantime. Second, I also made up my mind that even as I had to learn Sociology, I ought to make the best of the wider-scale learning that “America” potentially offered.

I also made considerable effort to link up the text with the nature of individual life – including my own, and the nature of society. One of the regrets I have is that I did not formally engage in field studies, develop a live and relatively intensive and prolonged relations with the people there (except for those within the university) and, thus, more extensively confront the text with the life and society I was participating in. But, to the extent possible, I attempted to “see” people and social relations in the survey data sets I analyzed and texts I read. It was a bit weird – reading people in sets of numbers and in texts. I consistently attempted, however, and to the extent it was possible, to conjure faces of people and the nature of social relations among them while I was interpreting the numbers and reading the texts.

One daring act I performed was that I “read” and learned a modicum of mathematics – mostly statistics, properly speaking. Recall that I was awfully weak and utterly scared of mathematics. But I could not imagine becoming a worthwhile sociologist without earning a modest level of knowledge and skills in statistics. I enrolled, first, in a class meant for the first-year undergraduate students. I failed in that course. I made that up with better grades in other courses. But I repeated the course again and, eventually, passed it with a “B” grade. I repeated the same story with another course in mathematics. (You can see here that failure has been my close companion for long.) Now, I feel good thinking back of the tribulations I went through. I can now personally carryout preliminary statistical analysis of data. More importantly, I can comprehend some statistical analysis that I read in books and journals. Most importantly, I am no longer fearful of preliminary mathematics – the kind that I am required to perform and interpret. More would be better. But I think I have done my part.

Professional life I (1978-1982)

I have led a rather long “reading kind” of professional life following my entry into the Tribhuvan University. I would not wish to bore you with a long version of it. Let me summarize it in four vignettes.

I read quite a lot during this early period of my professional career. The readings fell into two categories. The first category comprised of anything related to Nepal. I must confess right away that I was almost completely un-read, nearly illiterate, on Nepal, particularly for the kind of university life I has so willingly inserted myself into. My school and college level texts were extremely inadequate to comprehend the geography, polity, economy and culture of Nepal and of its presents and varied pasts. As such, I sought out and read whatever I could find on Nepal. Mostly though I read Nepal’s history – because there were more advanced history books and journals than any other at the time (except for literature that is, which I was not particularly interested in).

The second category of books I read was related to Marxism. A bookstore in Bhotahity, Kathmandu was a haven for books on Marxism. Because the publications were subsidized enormously by the Soviet Union books there were quite affordable. I bought and read or scanned maybe over a hundred of them over those four years. I learned quite a lot as well. But I also later learnt that much of Karl Marx (and Frederick Engels) in those books were, by means of omission, translation, etc., were Sovietized by the communist party there. There was no book on Maoism there, of course. But I was not after those either.

All this reading was good. It continues to be of great utility to me. What was really bad was that I did not publish a single piece during those four years – except for one book review. And, mind you, I was a researcher and a professor at that time. I have looked back at the period and said so many times to myself: Excellent in reading; a definite C in writing. Another failure to confront.

Professional life II (1983-1998)

The expanse of my reading was becoming wider – although I also kept the older categories alive. One huge and professional-life-changing process that started in 1986 was my entry into a new - rather esoteric at the time – way of thinking about the nature of the modern world and the nature of our life within it. This particular way of comprehending the world had begun to take shape during the mid-1970s. But I had remained almost oblivious to it. On the other hand, since the mid-1980s, I have, more or less, have remained wedded to this idea. This idea holds that even as the modern capitalist world is diverse and unequal it constitutes a single integrated commodity, labor and financial market. And this world, and its diversity and inequality along with it, keeps changing following a definite logic. (I should note here that I utilize capitalism as a descriptive rather than a laudatory or pejorative category that politicians of distinctive hues prefer.) Thus, I visualize the world, Nepal, my own self, etc., by utilizing this lens. I read fairly widely within social sciences, but I read more on this visualization tool than any other.

The other notable change in my “reading” began to take shape during and after following my brief nine-month stint in the government. One, it forced me to imagine, attempt to negotiate and implement what I – along with my colleagues – considered possible, instead of a dominant focus on critiquing not just the government but the nature of the state as such. It also forced me to visualize the whole of “Singha Durbar,” i.e., constitution and laws, central government, local government, bureaucracy, political parties, what fed democracy and what not, and so on and act on that basis. I had a seat close to the front not in terms of reading texts as such but in terms of intently viewing the whole of governance of Nepal and suggesting and acting where it looked promising. Inevitably perhaps, I also did some things that did not look promising to me. The experience also forced a recognition that good political practice, at least in relatively “normal times,” lay not zealously pursuing the very possibly unattainable best but the very possibly attainable good. That is, one bird in hand – and possibly a series of birds in hand - were way better than hundreds or more birds in the bush. All or nothing was an unworthy political gamble. The benefits of braiding that I have been speaking of came in extremely handy both to sift in the actual good and from the imaginary best as also to prepare a framework for implementing the good.

The final “reading” shift I made during this period was to both to read more Nepali texts more extensively and also to write in the Nepali language. The two, I think, went hand in hand. The rapidly blowing political wind of the late 1980s also lead me to this route. I certainly used to read Nepali language texts earlier but my ambit of reading in the Nepali language widened more thereafter. Writing in Nepali language, of course, gave me a host of gifts such as a much expanded readership, policy sensitivity, cultivation of new friendship, etc.

Professional life III (1999- Till Now Days)

The habit I was cultivating to braid text, life and society further intensified during this period. This came about, first, by means of the armed insurrection unleashed by the Maoists in Nepal. I had certainly read some about the theories of political change and revolution. I had also read about specific case studies of revolution. But I was not here reading about revolutionary theory and an actual case of revolution in a distant land. I was, this time around, living amidst a revolutionary insurgency that was sometimes labeled a “people’s war”. I was never in danger during the insurgency but in line with all of us, my movement and, to a certain extent voice, were circumscribed due both to the rebel insurgents and the government security forces.

The “Maoist interlude,” on the other hand, was a great opportunity for me to engage in a years-long and wide-scale reading of Maoism as such as well as the Maoist theory and practice in Nepal. I read about the rise of the rise and fall of Maoism the world over including in China and in Peru, which had shuddered under the Shining Path a decade back. I read up on the curious, incongruous, bhakti-laden and deadly hold that the one-man Revolutionary International Movement led by Bob Avakian enjoyed among the Maoists in Nepal. As in several other Nepal-related issues, it also led me to read about Nepal-India relations more deeply than I earlier had. In addition, I read about the UNMIN and several other associated international initiatives that were ostensibly designed to resolve the “Maoist problem”. Much more than these personal details, the more important point here is that the evolving nature of a society leads, almost forces one to engage with and read up on the why and how of the evolution and its variegated correlates.

Inevitably perhaps, I also read a considerable amount of literature on democracy and its various incarnations. Among others, I read about the social democratic form that has worked relatively well in Western Europe and Scandinavia. I also wrote up a couple of pieces on how constitution of Nepal, which was a consensus formed through intensive deliberations among most of the political parties in Nepal, had taken a social democratic direction and how taking this direction could prove immensely unifying and productive. It is sad that the political parties have almost called it quits on this front.

Four other categories of reading that I pursue these days are somewhat more disciplinary in nature, The fact that the categories are of disciplinary concern, of course, by no means implies that the readings possess no real-world implications. Let me take the four very briefly and in turn.

First, and this can be immediately be related to Nepal, is the promise and limit of capitalism. Capitalism, of course, has remained a whipping boy in our recent political history. Surely, capitalism, as any other ism that we know of, comes with salient limits. And, in the long run, my reading is clear that the kind of capitalism the world is enmeshed at present will either cease to be dominant or cease to exist altogether. The “end” is certain but what is uncertain is when. In the meantime, we live in the present, and we have to thrive now and not in an uncertain and unfathomed future. Democracy and citizens have to tame capitalism. But taming has to be intimately and actively responsive to what is taking place in the neighborhood and in the world. Taming, that is, must not lead either to stunting or to throttling.

The second one relates to the vantage point that everything around us is socially constituted. I read and sometimes write about how birth and death, which are seemingly exclusively biological phenomena, are also socially constituted at the same time. The point I am reading, thinking and much less frequently writing about is that there is nothing that is not a least partially socially constituted. This includes health and education, forestry and agriculture, information and fake news, and so on. It also includes, by the way, Covid-19, tuberculosis, enormous loss in the quality of education in Nepal during the last two decades, etc. That this disciplinary vantage point can be useful to grasp the real world is clear enough here.

The third one relates to another vantage-point question. This one has to do with the question of the relative primacy of agency on the one hand and history and structure on the other. Put more simply, this problematic can perhaps also be posed as whether an individual is more powerful or the more active doer than a society. I know this is somewhat of a chicken-or-egg question. And this, again, is a subject of huge and unsettled debate in Sociology. I have consistently sided with the primacy of society and history over an individual not the least because a child is conceived and born in a “pre-made” society the nature of which is independent of the newborn. Clearly, this is an interesting question in disciplinary terms. But it is also interesting and useful in real-world terms. For example, what ought to be the nature of the relations between a government and a citizen? How do we enhance the idea and practice of agentified citizenship in order to help and oversee the government? Or is agentified citizenship sick or dead in a political system where not the citizens but bureaucratized political parties distribute the spoils and have become dominant in almost all walks of life?

Finally, as I kind of hinted in the preceding paragraph, I have been reading and writing about the education system – mostly about the university but also about the school level. I have always believed that education is the primary instrument any society can wield to welcome better citizens and a better future. My readings do not tell me otherwise. I read about the kind of education that bears that kind of potential by sifting around the educational experience across the world. I feel sad that Nepal stands waist-deep in the muck in regard to education at all levels.

Closing

In closing, I suppose I will continue to read on issues tied to my four current engagements I just described to you. I find them intellectually significant and politically potent. But then life can take a turn and make you more interested in something else. I may well also submit to that possibility.

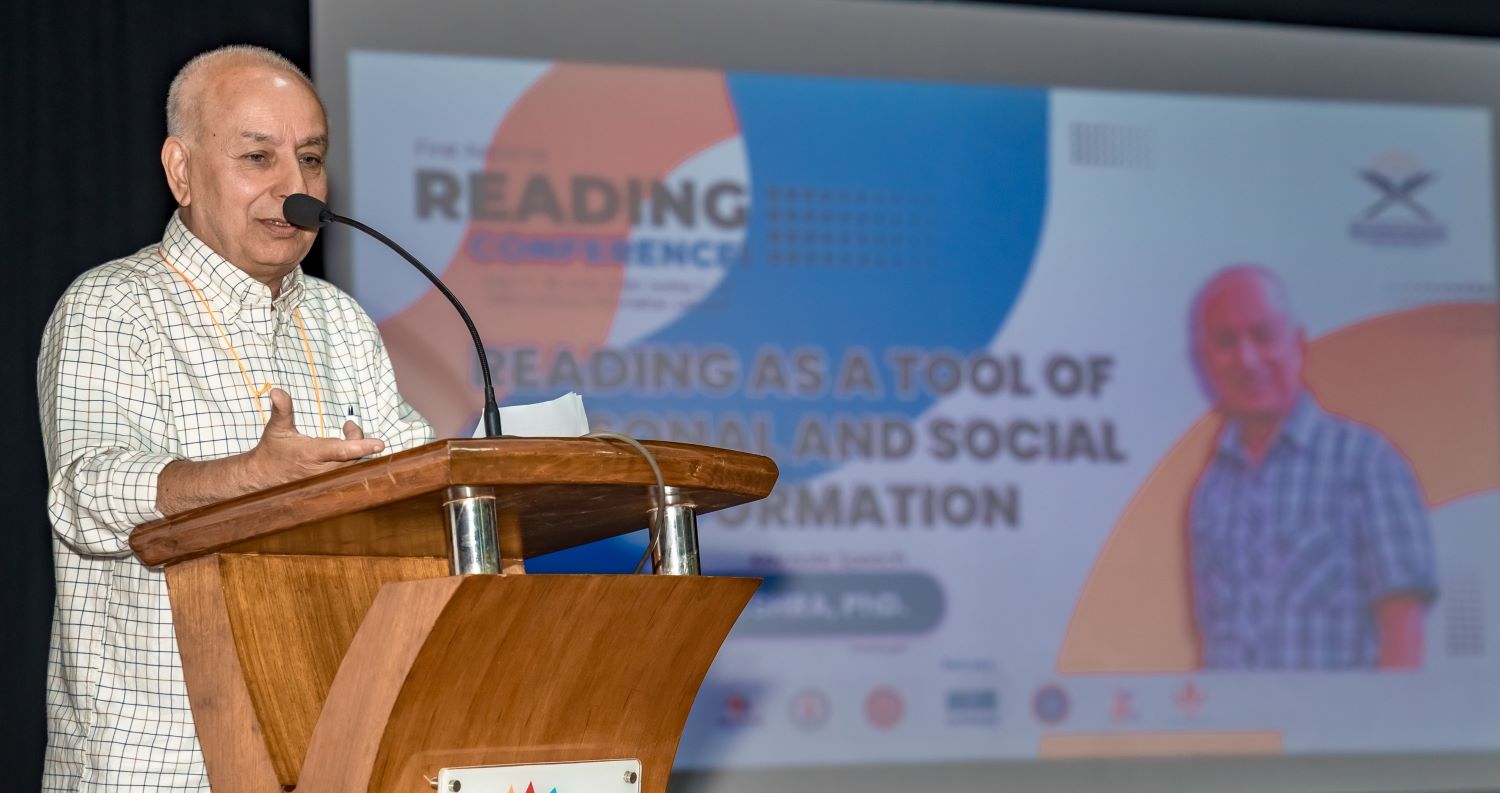

Views by Prof. Mishra as the keynote speaker at the first National Reading Conference recently held in Lalitpur.

प्रतिक्रिया